Oleh Eliyahu Ashtor

- Kata Pengantar

Artikel yang ditulis

oleh almarhum Eliyahu Ashtor (1914 – 1984), sejarahwan berdarah Austria –

Israel ini, sangat berharga untuk dibaca dan diketahui. Artikel ini aslinya

berjudul Spice

Prices in the Near East in the 15th Century,

dan dimuat pada Journal

of the Royal Asiatic Society, volume 108, isu 1,

Januari 1976, halaman 26 – 41. Sesuai judulnya, artikel atau makalah ini adalah

tentang harga-harga rempah-rempah yang beredar di pasar Levant atau di Timur

Tengah (Timur Dekat).

Kita memang

mengetahui tentang betapa bernilainya cengkih, salah satu dari rempah-rempah

itu. Namun, tidak banyak yang mengetahui berapa harganya, yang membuat

bangsa-bangsa Eropa begitu “tergila-gila” ingin mencari sumber rempah-rempah

tersebut. Melalui artikel sepanjang 16

halaman dan 168 catatan kaki inilah, Ashtor menyajikan daftar harga rempah-rempah

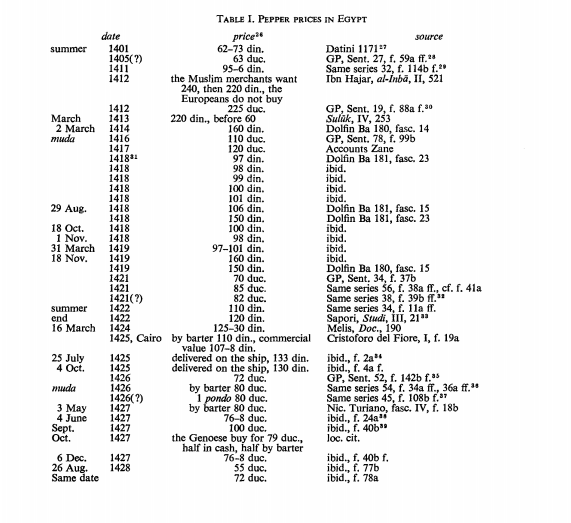

itu, termasuk cengkih dalam 9 tabel. Ada harga Lada, Kayu Manis, Jahe dan

Cengkih pada abad ke-15, bahkan yang paling tertua berasal dari tahun 1401. Ashtor

menyebut bahwa harga-harga yang ia sajikan itu, berasal dari sumber-sumber

Arab, dan dokumen-dokumen Italia.

Pasar dagang Levant,

bisa dianggap titik “terakhir” dari panjangnya perjalanan rempah-rempah dari

dunia timur ke Eropa. Dari sinilah, para pedagang Eropa memperoleh

rempah-rempah itu, dan ketika pusat perdagangan Mediterania ini diblokade, maka

Eropa “gelagapan”. Situasi demikian, yang akhirnya membuat Portugis dan Spanyol

berusaha mencari jalan, untuk menemukan asal rempah-rempah yang mereka

butuhkan.

Menganggap bahwa

kajian ini bermanfaat untuk diketahui, maka kami memberanikan diri untuk

menerjemahkannya. Beberapa ilustrasi kami tambahkan untuk “memperindah” artikel

terjemahan ini. Akhirnya, selamat membaca, semoga pengetahuan kita semakin luas.

- Terjemahan : Kutu Busu

Merupakan fakta yang

telah diketahui bahwa penemuan rute laut ke India, dan kelangkaan rempah-rempah

serta produk India lainnya di pasar Alexandria dan Damascus mengakibatkan

harga-harga rempah-rempah naik tajam. Dilihat dari sumber-sumber Venesia,

perubahan kondisi perdagangan Levant dianggap sebagai bencana besar. Di sisi

lain, beberapa sarjana telah menarik perhatian pada fakta bahwa harga lada

turun tajam di pasar Eropa, pada periode sebelum ekspedisi Vasco da Gama, dan

terutama pada kuartal kedua abad ke-151. Hal yang mungkin,

berdasarkan teori, bahwa ini disebabkan oleh tren penurunan harga di Timur

Tengah (Timur Dekat). Tetapi faktor-faktor lain, seperti tingkat permintaan di

negara-negara Eropa dan kondisi perdagangan (sistem hubungan dengan Timur

Tengah, perdagangan langsung atau tidak langsung), juga dapat mempengaruhi

harga rempah-rempah di Eropa2. Untuk menjelaskan dampak yang luar

biasa dari kenaikan harga rempah-rempah pada awal abad ke-16, saya (penulis)

telah menyarankan dalam buku saya Historie de prix et des salaires, kemungkinan

jatuhnya harga di kekaisaran Timur Tengah pada periode pra-Vasco Da Gama3.

Dalam makalah yang diterbitkan beberapa tahun sebelumnya, saya mencoba

memperkuat dugaan ini dengan bahan-bahan tambahan, dan selanjutnya, dengan

anggapan bahwa itu disertai dengan peningkatan besar dalam volume perdagangan

Levant, dan juga penurunan harga secara umum di Timur Tengah pada akhir abad pertengahan4.

Makalah ini mencakup

banyak data yang lebih lengkap, yang telah saya kumpulkan sebelumnya dari

berbagai sumber. Bahan-bahan untuk sejarah perdagangan Levant di Quattrocento

memang sangat banyak, sehingga memungkinkan untuk menyusun serangkaian lengkap

tentang harga, setidaknya dalam hal komoditas yang paling penting. Jadi makalah

ini memiliki dua tujuan : untuk mempublikasikan data baru, dan untuk menguatkan

hipotesis penurunan harga pada periode sebelum penemuan yang dilakukan oleh

Vasco da Gama5.

Beberapa data yang

terangkum dalam tabel-tabel berikut, saya temukan dalam kronik-kronik Arab,

tetapi sebagian besar diambil dari dokumen-dokumen Italia6. Banyak

yang berasal dari daftar harga yang dihasilkan oleh agen-agen perusahaan

Italia, yang lain berasal dari pernyataan resmi Giudici di petizion, sebuah

pengadilan untuk pedagang di Venesia.

Bagi sejarahwan

ekonomi, daftar harga dari periode yang diinginkan memiliki keuntungan luar

biasa. Kebanyakan dari daftar harga itu, memiliki tanggal yang tepat (tahun,

bulan dan hari), dan seringkali arsip-arsip dari perusahaan memuat surat dari

agen, yang ditulis pada hari yang sama, dimana ia memberi tahu pimpinannya

bahwa ia telah berhasil membeli sesuatu barang dengan harga lebih murah. Daftar

harga dalam Practica

della mercatura dari Giovanni da

Uzzano, bagaimanapun, sedikit bermasalah. Pada halaman judul, kita menemukan

tahun 1442, dan pada akhir tahun 1440. Tetapi beberapa data dalam buku itu

sendiri, telah menimbulkan keraguan pada bagian editor pertama, apakah penulis

memang mengumpulkan informasi tentang praktik dan kondisi komersial di zamannya

sendiri. Pagnini, editor buku itu, cenderung percaya bahwa ia telah menyalin

catatan yang dikumpulkan oleh orang lain, karena beberapa catatan yang ia

kutip, bertanggal tahun-tahun sebelumnya, pada masa sebelum ia dilahirkan7.

Mahasiswa yang tertarik pada bab-bab yang terkait dengan kondisi Timur Tengah,

harus memperhatikan fakta bahwa penulis tidak menyebutkan tentang ashrafi, yang

menjadi koin emas Mesir dan Suriah pada Desember 1425. Giovanni da Uzzano

merujuk harga di Mesir dalam dinar (bisanti), bernikai 1 – 1,3

dukat8. Namun, ini juga berlaku untuk Panduan Pedagang lainnya,

yang ditulis sekitar 8 tahun kemudian. Bahkan Libro di mercatantie

tidak mengetahui tentang ashrafi9.

Tanpa mempertimbangkan antara ashrafi dan dinar kanonik,

kita dapat menilai dari daftar harga Uzzano, bahwa indikasinya merujuk pada

periode 5 tahun sebelum dia menulis, atau mungkin bahkan 15 tahun.

Penjabaran data-data

yang terdiri dari catatan-catatan pengadilan disertai dengan berbagai

kesulitan. Sangat sering tanggal transaksi tidak disebutkan, dan di sisi lain, pengadilan

Giudici di petizion seringkali

terkait dengan proses pengadilan beberapa tahun sebelumnya. Jadi, kita harus mencoba

menetapkan tanggal dan mengidentifikasi pemilik-pemilik perahu, dimana barang

dagangan dikirim, atau menemukan orang lain yang mengambil bagian dalam

transaksi. Tak perlu dikatakan bahwa banyak tanggal yang ditetapkan dengan cara

ini, akan tetap bersifat dugaan. Lebih lanjut, acta peradilan

tidak memberikan tanggal dalam tahun tersebut. Tetapi seringkali, kita dapat

dengan aman menyimpulkan bahwa pekan raya rempah-rempah musim gugur tahunan

(yang disebut muda)

yang dimaksudkan. Kesulitan lain adalah sifat alami dari harga: kadang-kadang

subjek adalah harga yang dibayarkan di Levant, kadang-kadang harga di Venesia10,

termasuk semua biaya dan harga tara11.

Sejauh menyangkut

harga di pasar Levant, perbedaan harus dibuat antara harga bersih (tanpa bea

dan biaya lainnya) dan harga barang dagangan yang dikirim di atas kapal (spazado a marina)12.

Kita juga harus membedakan (seperti dilakukan dalam beberapa dokumen) antara

harga yang dibayarkan kepada pedagang Oriental/dari Timur (“da moro a franco”),

dan pembelian dari para pedagang Eropa lain di Timur Tengah (“da franco a franco”)13.

Kadang-kadang pihak

penuntut meminta jumlah yang jelas tidak sesuai dengan nilai barang dagangan.

Tujuan dari tindakan semacam itu adalah untuk melindungi klaimnya, dan pihak penuntutu

meminta bukan untuk nilai sebenarnya dari barang dagangan, tetapi untuk jumlah

resmi, misalnya 51 dukat14. Namun demikian, saya telah memperhatikan

semua data ini, dan dalam kasus dimana tidak ada yang lain, ditambahkan suatu

catatan, seperti referensi untuk pembebasan terdakwa.

Akhirnya pada

persoalan inti dari suatu bobot. Hampir semua data dari Suriah tampaknya

merujuk ke qintar Damascus,

yang terdiri dari 185 kg, menurut sumber-sumber Arab15, tetapi

menurut Panduan

Pedagang dan sumber-sumber Italia lainnya menjadi 600 pon

Venesia lebih ringan, yaitu 180 kg (tepatnya 180,73782 kg) atau bahkan kurang16.

Sangat sering harga pondo atau

collo (satuan

yang sama) yang dirujuk. Sejauh menyangkut kondisi Suriah, banyak dokumen

menunjukan bahwa itu setara dengan 50 – 52 ratls Damascus17.

Jadi kita dapat dengan aman menghitungnya sekitar 90 kg, atau setengah qintar Damascus.

Di Mesir, sebagian besar rempah-rempah dan barang-barang serupa ditimbang dalam

3 unit : qintar rempah-rempah,

sporta (bahasa

Arab, himl)

yang sama dengan 5 qintar rempah-rempah,

serta qintar dari

manns. Menurut

sumber-sumber Muslim, qintar rempah-rempah sama

dengan 45 kg18. Sumber-sumber Italia tampaknya setuju dengan

indikasi ini, meskipun ada perbedaan kecil, pedagang-pedagang Italia menganggapnya

agal lebih ringan daripada ang dilakukan oleh pedagang umat Islam19.

Akibatnya, ada perbedaan besar antara himl (5 qintar)

dan sporta. Bagi

para pedagang Italia, itu sama dengan 700 atau 720 pon Venesia lebih ringan,

yaitu 210,861 atau 216,8856 kg20. Sumber-sumber Arab menghitung mann Mesir

sama dengan 0,8125 kg21. Panduan Pedagang dari

Italia menunjukan padanan yang jauh lebih ringan22. Secara umum,

tampaknya sumber-sumber Italia menunjukan bobot nyata, sedangkan sumber-sumber atau penulis-penulis Muslim berbicara tentang

yang resmi. Dalam dokumen yang merujuk pada perdagangan dengan Mesir, muncul

juga pondo atau

collo. F.C.

Lane percaya bahwa itu sama dengan 1,12o pon Venesia23. Tetapi,

tampaknya dalam banyak dokumen akhir abad ke-14 dan awal abad ke-15, pondo ini

adalah dobel dari pondo Suriah

(90 kg), yang selanjutnya sekitar 4 kali lipat lebih banyak. Namun, berlawanan

dengan collo Suriah,

yang terakhir ini adalah unit yang agak samar-samar. Tidak ada kesimpulan,

karena itu harus diambil dari indikasi harga pondo seperti

itu24

Tabel-tabel

Tabel-tabel berikut ini memuat temuan saya

tentang harga rempah-rempah yang menempati posisi pertama dalam perdagangan

Levant, dengan kata lain barang-barang yang jumlah terbesarnya dikirim ke Eropa25.

Ini hanya terdiri dari data yang mengacu pada harga pasar, sedangkan jumlah

harga yang dipaksa dibeli oleh pedagang Eropa setiap tahun dari pemerintah

Muslim ditiadakan.

Kesimpulan

Tak

perlu dikatakan bahwa sejarahwan ekonomi haruslah diizinkan untuk memeriksa

data ini dengan berbagai cara. Harga biasanya lebih tinggi di musim gugur, di

periode muda148. Tetapi

harga rempah-rempah tidak hanya naik ketika para pedagang Eropa datang ke

pameran tahunan. Ada alasan lain mengapa harga rempah-rempah berfluktuasi,

seringkali, selama tahun itu (perhatikan harga lada di Alexandria pada tahun

1418, dan di Damaskus pada tahun 1412 dan 1413). Terkadang penyebabnya adalah

panen yang buruk atau hilangnya transportasi. Kadang-kadang ada perbedaan besar

antara harga produk tertentu di berbagai kota di negara yang sama149.

Harga yang lebih rendah diminta untuk dibayar tunai. Akhirnya ada harga

“bersih”, tidak termasuk berbagai biaya dan pengeluaran, dan harga yang lebih

tinggi dibayar untuk barang dagangan yang dikirim ke kapal (di pantai).

Perbedaan antara kedua harga itu, sebagian besar sekitar 10%150.

Data kami memungkinkan banyak jebakan, namun beberapa fakta memang muncul.

Sporta lada di Alexandria pada

tahun-tahun pertama abad ke-15 berharga 60-70 dinar, sama seperti pada akhir

abad ke-14151. Ketika al-Maqrizi mengatakan “ sebelum” harga sporta melonjak naik pada tahun 1413

menjadi 60 dinar, ia pasti memaksudkan pada tahun-tahun pertama abad ini.

Seperti yang ditunjukan data dari Damaskus, harga lada sudah mulai naik sebelum

tahun 1410. Di Alexandria, pada tahun 1411-1413, harga sporta naik menjadi 220 – 250 dinar. Dari tahun 1414 dan

selanjutnya, secara bertahap kembali harganya jatuh. Namun hingga tahun 1425,

harganya tetap sangat tinggi, mulai dari 100 hingga 160 dinar. Dari tahun 1426 –

1434, sporta lada harganya tidak

lebih dari 70 – 80 dukat. Pada tahun 1435 – 1437, kebijakan Sultan Barsbay

menghasilkan siklus pendek harga lebih tinggi, sporta mencapai 100 – 120 dukat152. Harga kemudian jatuh

ke 40 – 60 dukat pada dekade kelima abad ini. Dilihat dari harga lada di

Suriah, yang bergerak seirama dengan harga Mesir, siklus harga rendah ini

bahkan dimulai lebih awal, pada tahun 1439, dan berakhir setelah tahun 1450.

Data kami mengkonfirmasikan pernyataan di sumber kemudian yang merujuk periode

ini153. Itu berarti bahwa pada pertengahan abad ke-15, harga lada

lebih rendah daripada periode Fatimid154. Tahun 1458 – 1466 membawa

siklus pendek baru harga tinggi, sporta menjadi

90 – 100 dukat. Kemudian harga lada turun sekali lagi. Pada tahun 1471 – 1474, sporta lada di Alexandria harganya 60 –

70 dukat, tetapi pada tahun 1478 – 1497, harganya tidak lebih dari 50 – 60

dukat. Data baru mengenai harga lada di Suriah, misalnya merujuk pada muda tahun 1480 dan 1484155, mendukung

kesimpulan bahwa dalam periode segera sebelum perjalanan Vasco da Gama, harga

lada di pasar Timur Tengah sangat rendah156.

Data

yang telah saya tambahkan dalam makalah ini yang sudah diketahui mengenai harga

kayu manis menunjukan kenaikan yang cukup besar pada dekade kedua abad ini

(lihat harga di Beirut dan Damaskus). Di Mesir pada tahun 1411 – 1418, satu qintar dari manns sekitar 60-70 dinar. Namun pada tahun 1435, harga kayu manis

turun tajam. Di Mesir, harganya hanya 32 – 35 dukat. Di paruh kedua abad ke-15,

periode yang mana informasi kami sangat kurang, harga di Mesir tampaknya

sebagian besar lebih tinggi tidak sebanyak pada dekade kedua. Sedikitnya data

tentang harga kayu manis di Suriah pada periode terakhir ini, menyulitkan untuk

menarik kesimpulan.

Informasi tentang harga jahe

jauh lebih banyak. Ini menunjukan bahwa, seperti halnya rempah-rempah lain,

harganya sangat tinggi pada dekade kedua abad ini, satu qintar beledi di Mesir harganya sekitar 22 dinar. Tapi tampaknya

siklus harga tinggi itu, sudah dimulai sebelumnya, pada akhir abad ke-14. Data

dari Beirut dan Damaskus menunjukan dengan jelas fakta ini. Siklus ini berlangsung

hingga setidaknya tahun 1427. Lalu tren penurunan yang panjang terjadi. Pada tahun 1434-1435, para pedagang Italia dapat

membeli di Alexandria, satu qintar dengan

barter untuk 16-17 dukat, dan dengan uang tunai kadang-kadang bahkan untuk 10

dukat. Dalam tahun 1442-1444, harga rata-rata satu qintar adalah 14-16 dukat, dan setelah siklus harga tinggi pada

tahun 1470an, naik menjadi 25 dukat, pada tahun-tahun terakhir sebelum Portugis

mencapai India, turun menjadi 12-15 dukat. Jahe di Suriah ternyata selalu lebih

mahal, mungkin karena kualitas barang-barang itu yang lebih baik157.

Data baru pada tabel VI menunjukan bahwa harga masih tinggi di tahun 1428-1429,

satu collo menjadi 60 – 90 dukat.

Data dari tahun 1484 yang telah ditambahkan di sini, mengkonfirmasi laporan

dari tahun 1489158. Ini membuktikan bahwa di Suriah juga, harga dari

komoditas penting ini sangat rendah pada akhir abad ke-15.

Harga cengkih berbeda dari

rempah-rempah utama lainnya. Harganya turun jauh dan hampir secara progresif

mulai dari awal periode abad ke-15, tetapi pulih pada tahun 1440an ketika

rempah-rempah lainnya sangat murah. Kemudian harganya jatuh lagi (lihat data

dari Mesir pada tahun 1462 dan musim panas 1497). Jika item-item dalam Roteiro dapat diandalkan, bahkan akan

tetap menunjukan kejatuhan harga yang sebenarnya pada tahun-tahun sebelum

perjalanan Vasco da Gama. Kesimpulan ini akan didukung oleh data yang kami

miliki dari pasar Damaskus pada tahun 1480an.

Data dalam tabel kami menunjukan, bahwa perkembangan harga rempah-rempah di Eropa pada abad ke-15, berhubungan erat dengan pergerakan di pasar Levant. Juga muncul dari tabel kami bahwa harga rempah-rempah lain berkembang pada garis yang mirip dengan lada.

Data dalam tabel kami menunjukan, bahwa perkembangan harga rempah-rempah di Eropa pada abad ke-15, berhubungan erat dengan pergerakan di pasar Levant. Juga muncul dari tabel kami bahwa harga rempah-rempah lain berkembang pada garis yang mirip dengan lada.

Fluktuasi harga rempah-remah di

pasar Levant tercermin di Eropa. Lada menjadi lebih murah di mana-mana di paruh

kedua abad ke-15. Tren ini jelas terlihat dari data dalam dokumen-dokumen yang

merujuk pada harga di negara-negara yang jauh satu sama lain, seperti Perancis

Selatan159, dan Galicia160. Secara alami tingkat harga

rempah-rempah di Venesia, emporium besar komoditas ini, adalah yang paling

khas. F.C. Lane telah mengumpulkan harga lada di Venesia dari sejumlah

manuskrip161, sedangkan Magalhaes-Godinho telah menyusun dari Diarri milik Priuli, suatu daftar serupa

untuk tahun-tahun terakhir abad ke-15162. Tabel berikut memberikan

data tambahan mengenai harga grosir untuk merica, dan juga beberapa informasi

tentang harga jahe beledi.

===== selesai =====

Catatan Kaki

1.

A. H. Lybyer, "The Ottoman Turks and the routes of Oriental

trade", English Historical Review, XXX, 1915, 580, referring to the

data collected by Rogers and d'Avenel; F. C. Lane, "Pepper prices before

Da Gama",JEH, XXVIII, 1968, 590.

2.

Rightly stressed by Lybyer, loc. cit.

3.

Histoire des prix et des salaires dans

I'Orient medieval, Paris, 1969, 327.

4.

"La decouverte de la voie maritime aux Indes et les prix des

epices", in Milanges en Vhonneur de Fernand Braudel, Toulouse,

1973,1, 31 ff.

5.

If I found only a few additional items for the curve of the prices

of a certain product, I publish only these data. But if the new data, as

compared with those already known, are numerous, I compile a complete list. On

the other hand I quote several records from the one year indicating the same

price. As such records refer to different purchases they confirm each other.

Further, I include data in the tables which have been quoted (or printed)

erroneously elsewhere.

6.

The sources most often quoted are:

al-Maqrizi: al-Suluk, MS. Paris 1727. (Suluk 1727.)

ASV (Archivio di Stato, Venice), Senato, Deliberazioni miste. (Miste.)

ASV Giudici di petizi6n, Sentenze. (GP, Sent.)

ASV Cancellaria Inferiore, Notai, Ba 83, Cristoforo del Fiore. (Cristoforo del Fiore.)

ASV Cancellaria Inferiore, Notai, Ba 211, Nicolo Turiano. (Nic. Turiano.)

ASV Cancellaria Inferiore, Notai, Ba 230, Nicolo Venier. (Nic. Venier.)

ASV Miscellanea di carte non appartenenti ad alcun archivio, Ba 8, 29. (Miscell. di ness, arch.)

ASV PSM (Procuratori di S. Marco), Commissarie miste, Ba 128a, Com. A. Zane, fasc. V (cf. Hist. prix sal., 409 f.). (Zane.)

ASV PSM Com. miste, Ba 180, 181, Com. Biegio Dolfin. (Dolfin.)

ASG (Archivio di Stato, Genoa), Archivio Segreto 2774 C. (ASG 2774 C.)

ASP (Archivio di Stato, Prato), Quaderni di charichi e prezzi 1171, 1175. (Datini.)

Melis, F.: Documenti per la storia economica del secoli XJH-XVl, Florence, 1972. (Melis, Doc.

al-Maqrizi: al-Suluk, MS. Paris 1727. (Suluk 1727.)

ASV (Archivio di Stato, Venice), Senato, Deliberazioni miste. (Miste.)

ASV Giudici di petizi6n, Sentenze. (GP, Sent.)

ASV Cancellaria Inferiore, Notai, Ba 83, Cristoforo del Fiore. (Cristoforo del Fiore.)

ASV Cancellaria Inferiore, Notai, Ba 211, Nicolo Turiano. (Nic. Turiano.)

ASV Cancellaria Inferiore, Notai, Ba 230, Nicolo Venier. (Nic. Venier.)

ASV Miscellanea di carte non appartenenti ad alcun archivio, Ba 8, 29. (Miscell. di ness, arch.)

ASV PSM (Procuratori di S. Marco), Commissarie miste, Ba 128a, Com. A. Zane, fasc. V (cf. Hist. prix sal., 409 f.). (Zane.)

ASV PSM Com. miste, Ba 180, 181, Com. Biegio Dolfin. (Dolfin.)

ASG (Archivio di Stato, Genoa), Archivio Segreto 2774 C. (ASG 2774 C.)

ASP (Archivio di Stato, Prato), Quaderni di charichi e prezzi 1171, 1175. (Datini.)

Melis, F.: Documenti per la storia economica del secoli XJH-XVl, Florence, 1972. (Melis, Doc.

7.

Pagnini, Delia decima, Lisbon, Lucca, 1765-6, II, 78. As to

the prices themselves see the remarks of C. Trasselli, "Produzione e

commercio dello zucchero in Sicilia dal XIII al XIX secolo", Economia e

storia, III, 1955, 334.

8.

p . 111.

9.

El libro di mercatantie et usanze de'

paesi, ed. Fr. Borlandi, Turin, 1936, 81.

10.

In the pleadings of a lawsuit, GP, Sent. 129, f. 58b ff., the

defendant Polo Mudazio is described as patron of a galley to Beirut in 1454 on

which the merchandise (pepper) was shipped. But according to Senato, Mar Reg.

IV, f. 189a, he was patron in 1453, whereas his name does not appear in the

list of the patrons of 1454. In a passage of the plea of the defendant one in

fact finds the date 1453. Certainly this error can be explained by the fact

that the accounts were made according to prices in Venice, where the merchandise

was sold in 1454. The tribunal in fact establishes the price of a carica, sc.

in Venice (f. 59b). So the deeds refer to the price in Venice.

11.

See GP, Sent. 98, f. 75b f.; 99, f. 12b ff.; 129, f. 58b ff.

12.

See GP, Sent. 100, f. 40a,

and see below.

13.

Melis, Doc, 186.

14.

See GP, Sent. 48, f. 52b f.; 17, f. 54a f.; 20, f. 20a f.; 100, f.

6a ff.; (salvo drieto).

15.

W. Hinz, Islamische Masse und Gewichte, Leiden, 1955, 30.

16.

Uzzano, 113, actually has 620 libbre sottili, but see Tarifa

zoe noticia deipexi e mexure, Venice, 1925, 26, 64; // manuale di

mercatura di Saminiato di Ricci, ed. A. Borlandi, Genoa, 1963, 35; Libro

di mercatantie, 147; GP, Sent. 19, f. 66a f.; 114, f. 75a; 181, f. 123a,

etc.

17.

ASV Giudici di petizi6n, Terminazioni VII, f. 21b, 26a, 32b, 47a,

89b, 92b; VIII, f. 48a, 48b, 50a; 11, f.

98a, 109b, 165b; 12, f. 98a, 101a, 107b; 13, f. 30a, 96b, 97b. J. Heers concluded that the collo was equal to 91 kg., see // commercio nel Mediterraneo alia fine del sec. XIV e mi primi anni del XV, ASI, CXIII, 1955, 184, whereas Lane found that it was only 290 Venetian pounds, cf. "Venetian shipping during the commercial revolution", in his Venice and history, Baltimore, 1966, 13.

98a, 109b, 165b; 12, f. 98a, 101a, 107b; 13, f. 30a, 96b, 97b. J. Heers concluded that the collo was equal to 91 kg., see // commercio nel Mediterraneo alia fine del sec. XIV e mi primi anni del XV, ASI, CXIII, 1955, 184, whereas Lane found that it was only 290 Venetian pounds, cf. "Venetian shipping during the commercial revolution", in his Venice and history, Baltimore, 1966, 13.

18.

Hinz, op. cit., 29.

19.

Pegolotti, ed. Evans, 75, has the equation with 139 Genoese pounds

(44-02825 kg.), Libro di mercatantie, 140, with 133-33 Genoese pounds

(42-23222775 kg.), but p. 76 with 150 light Venetian pounds, i.e. 45-1845 kg.

In GP, Sent. 129, f. 153a ff., it is said to equal 144 light Venetian pounds,

i.e. 43-37712 kg.

20.

Uzzano, 109; Libro di mercatantie, 76; Tarifa, 28,

60 all have 720 libbre sottili. Pegolotti, 7 1 , says t h a t cantari

2\ gervi di zucchero are considered the same weight as a sporta, a n

d as th e qintar jarwi, according to the Italian sources, consisted of

90 kg., the sporta would have been 225 kg. M a n y other sources

indicate, however, 700 Venetian pounds as the equivalent of the sporta, see

A . Sapori, Studi di storia economica, Florence, 1955-67, III, 2 1 ; G P

, Sent. 105, f. 136b ff.; 108, f. 7 0 b ; o r 710 pounds, cf. G P , Sent. 34,

f. 37a ff.

21.

Hinz, op. cit., 16.

22.

Pegolotti, 74, has the equation 2-65-2-68 libbre sottili, i.e.

O-7982595-O-8072964 kg., but both Uzzano, 112, a n d Libro di mercatantie,

11 have 2 - 5 libbre sottili, i.e. 0-753075 kg.

23.

loc. cit.

24.

The only relevant text among those quoted by Lane which

substantiates his conclusion is ASV Senato,

Mar Reg. 12, f. 136b, a decree of 20 March, 1488 concerning a deposit to be paid pro quolibet collo

26 alexandrino due. 2, pro quolibet collo damascheno due. i. See also Lane in JEH, XXVIII, 1968, 591 n. 6.

Mar Reg. 12, f. 136b, a decree of 20 March, 1488 concerning a deposit to be paid pro quolibet collo

26 alexandrino due. 2, pro quolibet collo damascheno due. i. See also Lane in JEH, XXVIII, 1968, 591 n. 6.

25.

If there is no other indication, the Egyptian price-tables refer

to the market of Alexandria, and the Syrian to Damascus. Collecting data from

the acts of the Giudici dipetizibn, I quote, as far as possible, in the

tables the prices fixed by the tribunal, whereas the prices claimed by the

litigants are relegated to the notes.

26.

If there is no other

indication, it is the price of a sporta.

27.

A list of various articles bought by the Venetians in 1401 till 27

September. Therefore the price-range is wide.

28.

The reference being to a lawsuit pleaded in July 1407, one may

suppose that the transaction dated from not later than 1405 (and possibly

earlier). The merchandise had been transported to Venice on a cog whose patron

was Marco de Benedetto. In the pleadings one reads that 970 Venetian pounds

were worth

85 ducats. Accordingly the price of a sporta was 63 ducats.

29.

The defendant says that one also paid 220 ducats.

30.

This is the price fixed by the law-court (40 ducats and 11 grossi

ad aurum for 116 pounds). The plaintiff says that the price was 330 ducats

(53 ducats for 116 pounds). According to the register of the litigation pleaded

on 19 August, 1413 the transaction was made at the preceding muda. Nicolo

Memo, who bought the pepper, was certainly in Alexandria in 1412, cf. GP, Sent.

336, f. 56a ff. On the other hand one reads in the pleadings that the pepper

was shipped on a galley of "Pietro fil. Alban Contarini" (in the MS

only "Pietro dmni Albani", without "Contarini"). He was in

1409 and in 1412 patron of a galley going to Alexandria, cf. Miste 48, f. 84a,

49, f. 127a.

31.

Many notes in the Dolfin archives have no exact dates.

32.

The litigation pleaded on 19 March, 1426 refers to the activities

of a company " per aliquantum temporum " . The sporta is here

called "cargo", cf. Hist, prix sal., 324 n. a. In fact

the names of the weights are often confused.

33.

On the date cf. M . E. Mallett, The Florentine galleys in the

fifteenth century, Oxford, 1967, 26.

34.

p sporta expedita sup nave.

35.

By an error the price is said to be that of a qintar.

36.

In the text quoted in the first place the unit of weight for which

the said price had been paid is erroneously called zpondo. But the fattore

claims that the real price was 100-5 ducats a sporta.

37.

Pleadings, on 16 August 1428, of a lawsuit against Marco

Contarini, patron of the galley on which the merchandise has been shipped. This

name is not to be found on the registers of the Senate referring to the years

preceding 1428. But the name Constantino Contarini appears as patron of an

Alexandrian galley

in 1423 and in 1426, cf. Miste 54, f. 118b and 56, f. 36a.

38.

I quote the date of the document, but the transaction itself had

been made earlier.

39.

This is not the market price. The Venetian Bartolomeo Bembo wants the

said amount from a Sicilian merchant who was very eager to barter a certain

quantity of sugar.

40.

Lawsuit pleaded on 30 November 1430.

41.

The plaintiff claims at first that the price of 714 ratls was 155

ducats, the defendant says 185 ducats, and finally the plaintiff confesses that

the price was 180 ducats. According to the latter statement the price of a sporta

was 125 ducats, but the defendant is acquitted.

42.

The plaintiff claims 42.

43.

Dubrovnik et le Levant, Paris, 1961. A s this

price was stipulated for a delayed payment, the market price was probably

lower.

44.

Lawsuit pleaded on 26 March 1444.

45.

A lawsuit pleaded on 10 February 1445. The pepper had been sold by a

Venetian to a fellow-countryman.

46.

Lawsuit pleaded on 12 January 1445.

47.

The merchandise had been resold on the sea-shore for 51 ducats.

48.

The plaintiff says that the price was 50 ducats, the defendant asserts that

others bought for 97.

49.

Lawsuit pleaded on 19 April 1451.

50.

Lawsuit pleaded on 2 April 1446.

51.

The plaintiff: 100 ducats.

52.

The plaintiff had asked for 100 ducats.

53.

The plaintiff: 61 ducats.

54.

The plaintiff: 66-7 ducats. The sum fixed by the tribunal is the price of

700 Venetian light pounds, so58 that a sporta of 720 would have amounted

to 57-7 ducats.

55.

Lawsuit pleaded on 26 May 1463.

56.

Lawsuit pleaded on 27 May 1465.

57.

In the text quoted in the first place different prices are indicated, the

average being 70 ducats. In the other text, which refers to the same

transaction, one reads that the pepper had been bought from the"merchant

of the sultan" at 70 ducats, which was surely the market price, and later

resold by the fattore at the same price.

58.

Price at which pepper was sold by the Genoese consulate.

59.

See n. 58 above.

60.

See n. 58 above.

61.

A purchase made by the consulate from an Italian merchant.

62.

A purchase made by the consulate from an Italian merchant.

63.

A purchase by the consulate.

64.

A purchase by the consulate from an Italian merchant.

65.

Although this entry refers to a purchase from the "emir", it is

the market price.

66.

This is the price at which the consulate sells the quantity of pepper

bought from the "emir".

67.

The price includes duties.

68.

Lawsuit pleaded on 7 March 1486 concerning the barter of wheat of Cyprus at

a high price against pepper. Vittore Marzello, the archbishop of Cyprus who

bought the pepper, occupied the see from 7

February 1477 to 2 January 1484, see C. Eubel, Hierarchia Catholica medii

aevi, II, Miinster, 1914, 203. On the

other hand, in the years 1479-83 pepper was cheap and in 1480 wheat was also,

see 'Abd al-Basif b. Khalil, Nail al-amal, MS

Bodl. 812, f. 300b.

69.

Reyssbuch des heyligen Lands, Francfort, 1609.

70.

One reads in the pleadings dated 18 May 1489 that the pepper was shipped on

a galley belonging to the convoy whose captain was Marco Gabriel. According to ASV

Segretario alle voci VI, f. 83a, he was captain

of the Alexandria galleys in 1487. The patron of the galley was Fantin

Arimondo, whose name in fact figures on the

list of the patrons of 1487, see ASV Incanti I, f. 122b.

71.

The text does not give the price. One reads, however, that a Venetian

company sold olive oil, imported in Alexandria, at two

prices: 11 qinfars for a sporta pepper and \1\. As the price of a

qintar (jarwi) of European oil was then

probably 6 ducats, a sporta was worth 66 ducats. For the price of

oil see Hist, prix sal., 319.

72.

According to the plaintiff the price amounted to 60 ducats only.

73.

Roteiro da viagem de Vasco da Gama en 1497, 2nd ed., Lisbon,

1861. The exchange rate of the cruzado was almost equal to the

ducat, see A. Weitnauer, Der venezianische Handel der Fugger, Munich,

Leipzig, 1931, 61. If the author had the Portuguese

quintal (58-752 kg.) in mind, the price would have

been rather lower.

74.

This was not the market price, see Melanges Braudel, I, 45 n. 31.

75.

According to Pegolotti, 101, the qintar of Ramla was equal to 1,12

quintal of Cyprus, i.e. 252,6333423 kg.

76.

The date of the purchase is not indicated, but according to the register of

the litigation pleaded on 9 February 1417, the merchandise h a d been shipped o n a

galley whose patron was Jacobus Barbadico.This name appears on the list of the

patrons of the Beirut galleys in 1412,1413, and 1416, cf. Miste 49, f. 126a 50, f. 5b 51, f. 137a. The price indicated in the

text, however, corresponds to those of 1412.

77.

Another lawsuit concerning a shipment on the galley of Giacomo Barbarigo.

For 53-5 ratls the sum of 60 ducats was demanded, but

not accepted by the tribunal.

78.

To be corrected in Hist, prix sal., 411, from 14 August 1413.

79.

In the text quoted in the first place one reads: ratV 63 val

circa . . . due' 96 gr' 3(?), and in the other text: ratl'

62 one' 9 - due' 96.

80.

The plaintiff h ad asked for 84 ducats.

81.

A letter from Rhodes dated 3 October 1417. The writer asks his

correspondent to buy at this price. So the price after the muda is meant.

82.

To be corrected from dm (dirhams).

83.

In the pleadings a lower price is indicated, viz. 55 ducats.

84.

A lawsuit pleaded on 14 February 1428.

85.

The Venetian merchant for w h o m the fattore bought the

pepper had allowed him to buy at 88-99 ducats.

86.

This was the amount asked for by the plaintiff. The court absolved

the defendant.

87.

Two litigations (action and counter-plea) referring to the same

transaction. In the register of litigations pleaded in 1430 (without exact

date, probably in March) the date of the transaction is not given. But one

reads that the merchandise was loaded on a galley whose patron was Andrea

Tiepolo, and according to Miste 57, f. 118b he conducted a galley to Beirut in

1429.

88.

A lawsuit pleaded on 7 March 1430. The merchandise had been

shipped on the galley of Bertuzio Dolfin.

He was patron of a Beirut galley in 1425, 1426, and 1429, see Miste 55, f. 148b 56, f. 36a 57, f. 118b. The price corresponds to the data from 1429, but it is not impossible that the text refers to 1426. In 1425 the price was apparently higher.

He was patron of a Beirut galley in 1425, 1426, and 1429, see Miste 55, f. 148b 56, f. 36a 57, f. 118b. The price corresponds to the data from 1429, but it is not impossible that the text refers to 1426. In 1425 the price was apparently higher.

89.

A lawsuit pleaded on 9 February 1437 referring to pepper bought in

Damascus. The price indicated in the table is the price brutto (computatis

expensis et provisione), which means the expenses in Damascus as fixed by

the tribunal. The plaintiff had asked for 56-4 ducats, whereas the defendant

maintained that he had sold to others for 69 ducats.

90.

With the expenses in Damascus the price amounted to 75 ducats.

91.

4 qintars had been bought at 47-5 ducats each. The qintar

of Tripoli was equal to the Damascus qintar, cf. Pegolotti, 90, 91.

92.

A lawsuit pleaded on 31 July 1438.

93.

A lawsuit pleaded on 30 May 1438. It is not stated that the pepper

had been bought in Damascus, but there can be no doubt of it.

94.

The price does not include expenses. With them (but without the freight)

it would have been about 6 ducats more. Payment had been half in cash, half by

barter. The defendant claims that paying in cash one could have bought at 35

ducats. If the qintar spoken of was the qintar of Acre, being 226

kg. (see

Pegolotti, 67), the Damascus qintar amounted to 36 ducats only.

95.

At this price the Venetian cottimo sells the pepper.

96.

The plaintiff asked for 51 ducats, the price without expenses.

97.

A litigation between Franco Dolfin and his fattore Fantin

Bon, pleaded on 22 August 1461 and referring to the purchase of pepper in

Damascus. Franco Dolfin was in Damascus in 1460, see Cristoforo del Fiore, VI,

f. [la]f., but in the pleadings of the lawsuit one finds, f. 166a, the date

1458. In this latter year the pepper was, however, much more expensive (see

above). Further one reads in the register: "/> resto di pip r"

11 io le di a Damascho due' 11", a statement probably referring to a

purchase at another date.

98.

See in Mdlanges Braudel, I, 45 n. 39. Another entry of this

purchase is to be found in his accounts in Miscell. di ness. arch. Ba 8, fasc.

8. The note concerning the purchase from the sultan in 1475 for 104-5 ducats,

ASV PSM Com. m. Ba 116 fasc. 7 (cf. Milanges Braudel, I, 35) undoubtedly

refers to a

price fixed arbitrarily by the Mamluk government.

99.

A lawsuit pleaded on 4 March 1485. T he a m o u nt listed in the

table is the price asked for by the plaintiff.

Since the merchandise had been sequestered at the Customs office in Venice it is the brutto price. The action is refused by the court. So n o conclusions can be drawn from the text.

Since the merchandise had been sequestered at the Customs office in Venice it is the brutto price. The action is refused by the court. So n o conclusions can be drawn from the text.

100.

Hist, prix sal., 410,

notes.

101.

The merchandise h a d been resold at the price listed in the table

in Damascus . The lawsuit was pleaded on 30 June 1486.

102.

The kinds of cinnamon which are most often mentioned in our

documents are the following: (a) canella lunga or fina; (b) salani (from

Ceylon) or mezzana; (c) mabari (from Malabar) or grossa, cf.

Heyd, II , 597 f. The name of the second kind appears in the list of Uzzano,

112, as senelli and 114 as salami.

103.

The unit of weight whose prices are listed in the table is the qintar

of manns. cf. above, n. 27. T h e note refers to various kinds of

cinnamon.

104.

The register of the lawsuit, pleaded on 10 February 1417, does not

include the date of the purchase. It

does mention, however, the patron of the galley on which the merchandise was shipped: Joh. Gradenigo.

According to Miste 51, f. 136a, he was p a t r o n of an Alexandrian galley in 1416.

does mention, however, the patron of the galley on which the merchandise was shipped: Joh. Gradenigo.

According to Miste 51, f. 136a, he was p a t r o n of an Alexandrian galley in 1416.

105.

A lawsuit pleaded on 30 November 1430.

106.

Accounts of transactions in Alexandria in 1444-5. T h e item

reads: el canter [sc. 100 Venetian pounds!] due' 15.

107.

There is no date of the transaction in the register of the

lawsuit, pleaded on 30 May 1461. But Piero Morosini, who demands payment for

spices bought by him in Alexandria, went there in 1460, see G P , Sent. 133, f.

39b ff., and cf. 135, f. 132a ff.

108.

cf. Hist, prix sal., 412 ff.

109. The register of the lawsuit pleaded on 10 June 1413 does not

contain the date of the transaction. Benedetto

Dandolo, who made the purchase in Damascus, was there in 1411 (see Hist, prix sal, 415) and in 1412 (see Giacomo della Torre, ASV Notarile 14832 no. 2 (31 March 1412)). The plaintiff, who had left the merchandise to be sold, was there in 1411, see GP, Sent. 32, f. 30b ff. There is an error in the account: 174 Venetian pounds equal 28, not 18 Damascene rathls

Dandolo, who made the purchase in Damascus, was there in 1411 (see Hist, prix sal, 415) and in 1412 (see Giacomo della Torre, ASV Notarile 14832 no. 2 (31 March 1412)). The plaintiff, who had left the merchandise to be sold, was there in 1411, see GP, Sent. 32, f. 30b ff. There is an error in the account: 174 Venetian pounds equal 28, not 18 Damascene rathls

110. A lawsuit pleaded on 3 April 1417.

111. See above, n. 81.

112. To be corrected in Hist, prix sal., 414.

113. The text reads erroneously "75". But as the price of 230 rails

is 210 dinars, it must be 91-3.

114. cf. Heyd, II, 599.

115. When not otherwise indicated, the price listed is that of a qintar of

45 kg. If the kind of ginger is not

116. See above, n. 27. One reads in the text: "ginger of all kinds". specified in the source, I assume that it is beledi ginger.

117. The sum quoted in the table was stated in the deed to be the market price,

but it deals with a purchase

118. A lawsuit pleaded in August or September 1428. by barter at the price of 15

dinars.

119. As to the following quotations from the deeds of Nic. Turiano see my paper

in Milanges Braudel, I, 37, and nn. 45-50.

120. The defendant claimed that the ginger was acquired for 8-5-9 ducats. The

verdict of the court was a compromise: the defendant must pay for the greater

part of the merchandise due. 7 gr. 12 and for a smaller part (the sieved

ginger) the market price in Venice.

121. A lawsuit pleaded on 28 August 1444.

122. As to the date, see above, n. 107. The defendant says that the beledi cost

only 14 ducats.

123. The price listed in the table is the sum asked by the plaintiff. The date

of the transaction is not indicated. But Marco Morosini (fil.

Zuan), who shipped the ginger from Alexandria, was there in 1461, see G P Sent.

150, f. 49a ff., and the lawsuit was pleaded on 10 July 1462.

124. The price quoted in the table is claimed by the defendant. The plaintiff

asserts that the ginger had been bought for 23 ducats.

125. This is the price asked for by the plaintiff.

126. A lawsuit pleaded on 10 February 1491

127. The pleadings refer to ginger transported to Modon on a galea di

traffico, but there can be no doubt that an Alexandrian collo is

meant.

128. cf. Hist, prix sal, 414 ff.

129. Although n o date is mentioned in the register of the lawsuit pleaded on 14

January 1416, it can easily be established. Nicolo Dolfin, who had given the

order to invest a great sum in the purchase of ginger when he was captain of

the Cyprus galleys, held this post in 1409, cf. Cronica Morosini, M S

Vienna, the Foscarini 234 (6584), f. 230a (179b).

130. The price is 1,935 dirhams. According to the price-lists Zane on 10 October

1411 (in Damascus) exchange rate was 51 dirhams to the ducat, but here

apparently other (sc. Hamath) dirhams are meant. In fact one finds the exchange rates 31, 31-33, 32, 35, 36

dirhams in accounts of Donado Soranzo from the years 1414-18.

131. The price is 2,009 dirhams. The exchange rate was according to the said

lists on 10 March 1412,90 dirhams to the ducat.

132. d. in the MS means dirhams.

133. Seen. 81.

134. Pleadings of a lawsuit on 4 June 1428.

135. The date is uncertain. The plaintiff says that the defendant began to send

him merchandise in 1428

136. See above, n. 88 and below, n. 137. Polo Barbarigo, the defendant who sent

the merchandise from Beirut, was there in 1429, cf. G P

, Sent. 54, f. 63b, and Miste 57, f. 118b. The sum quoted from the pleadings,

whose date is probably February 1430 is the price asked for by the plaintiff.

There is no decision.

137. See above, n. 88. The price is what the plaintiff demanded;there is no verdict.

The pleadings have no date, probably it was June or July 1430.

138. The plaintiff had asked for 150.

139. In fact the place where the ginger had been bought is not mentioned in the

pleadings, but it is much more probable that it was Damascus than Alexandria.

140. A lawsuit pleaded on 28 August 1445. I conclude that it referred to a

transaction in 1440 (approximately), because the "Syrian"

dirham is calculated at & ducat. This was the exchange rate in 1440,

see GP, Sent. 84, f. 123a f., whereas it was

40 in 1443, see same series 112, f. 63b.

141. A lawsuit pleaded on 30 June 1486.

142. A lawsuit pleaded on 31 November 1430.

143. A lawsuit pleaded on 10 February 1445.

144. The pleadings have "ratl", but this is surely an error

(for mann).

145. cf. Hist, prix sal., 471 f.

146. To be corrected in Hist, prix sal., 418 (from "1417").

147. L 1131 onze 1 bought for L 37 s 6 d 7/28.1 have calculated the price of the

Damascene qintar accordingly.

148. See Nic. Venier B, 2, f. 9b f.: etnerat (piperem) adpretium quo

venderetur ad terminum galearum Venetorum ad viagium Baruti mude pres. See

also G P , Sent. 76, f. 47a.

149. See the prices of beledi ginger in Syria in 1411-12 listed above and cf. Hist.

prix. sal., 415.

150. See above in the notes on pepper prices in Egypt in July 1425, 1444.

151. See my paper "La decouverte de la voie maritime" , 36.

152. The rise of the pepper price in the last years of Barsbay's reign

is clearly indicated by the data from Venice, see below sub anno 1436

and in the table of Lane, art. cit., 594.

153. Marino Sanuto VII, col. 218; Tauflq Iskandar, Ni?am

al-muqdyaa'a fi tijdrat Misr al-kharijiya, in alMajalla al-ta'rikhlya

al-misriya, VI, 1957, 43.

154. See Hist, prix sal., 138 f.

155. The data which I have collected do not confirm the opinion of

Lane, art. cit., 590 concerning the level of prices in the 1470's. On the N e a

r Eastern markets they were certainly higher than in the 1440's. As to prices

in Syria in the '80's see Hist, prix sal., 412. The difference between

the price of pepper in Alexandria and in Damascus is smaller if the Damascene qintar

is considered equal to 180 kg.

156. Contrary to the mistaken statement of S. Y. Labib concerning the

rise of the pepper price in Egypt in the 15th century, see his Handelsgeschichte

Agyptens im Spdtmittelalter, Wiesbaden, 1965, 438. It should be stressed

that even the price of those quantities which the Venetians had to buy from the

sultan forcibly (upon which Labib erroneously relies) went down !

157. Therefore at the end of the 14th century and in the first half of

the 15th century European merchants bought m o r e ginger in Syria than in

Egypt, see J. Heers, // commercio nel Mediterraneo, 168,172,174, 175; my

Les metaux pre'cieux et la balance des payments du Proche Orient a la basse

epoque, Paris, 1971, 74; L a decouverte de la voie maritime, 38, Table V I

I ; "Venetian supremacy in the Levantine lbe trade—monopoly or

pre-colonialism?", /. European Economic History, III, 1974, 36 f.

158. Hist, prix sal., 416.

159. E. Baratier and F . Reynaud, Histoire du commerce de Marseille,

II, Paris, 1951, 388.

160. J. Pelc, Ceny w Krakowie w latach 1369-1600, Lwow, 1935,

42, and cf. M . Malowist, "Les routes du commerce et les marchandises du

Levant dans la vie de la Pologne au bas Moyen Age et au debut de l'epoque

moderne", in Mediterraneo e Oceano Indiano, Atti del sesto colloquio

intern, di storia marittima, 1962, Florence, 1970, 167.

161. art. cit., JEH, XXVIII, 1958, 594 f.

162. Viconomie de I'empire portugais aux XV* et XVIe siecles, Paris, 1969, 719 f.

163. Almost all the data which I have found in the registers of the Giudici

dipetizibn and certain other sources refer to years for which Lane has no

items. But some are taken from the letters to Biegio Dolfin which have also

been quoted by Lane. The eminent American scholar, however, quotes another part

of the Dolfin archives, namely Ba 181, whereas I also use the numerous documents

in Ba 180. This folder in fact contains some price-lists which the Italian

merchants used to compile for various emporia.

164. A lawsuit pleaded on 15 October 1457.

165. Accounts of the company of Andrea Zorzi and the family Marino

Sanuto, the latter partners being the "fraterna" Giacomo, Paolo and

Lionardo, sons of Marino Sanuto.

166. K. J. Miiller, Welthandelsbrauche {1480-1540), Wiesbaden,

1962. But see there 186: 50-2 ducats!

167. Lawsuit in 1458.

168. A lawsuit in 1482. It is possible that the amount asked for is not the

price, but simply compensation.

Tidak ada komentar:

Posting Komentar